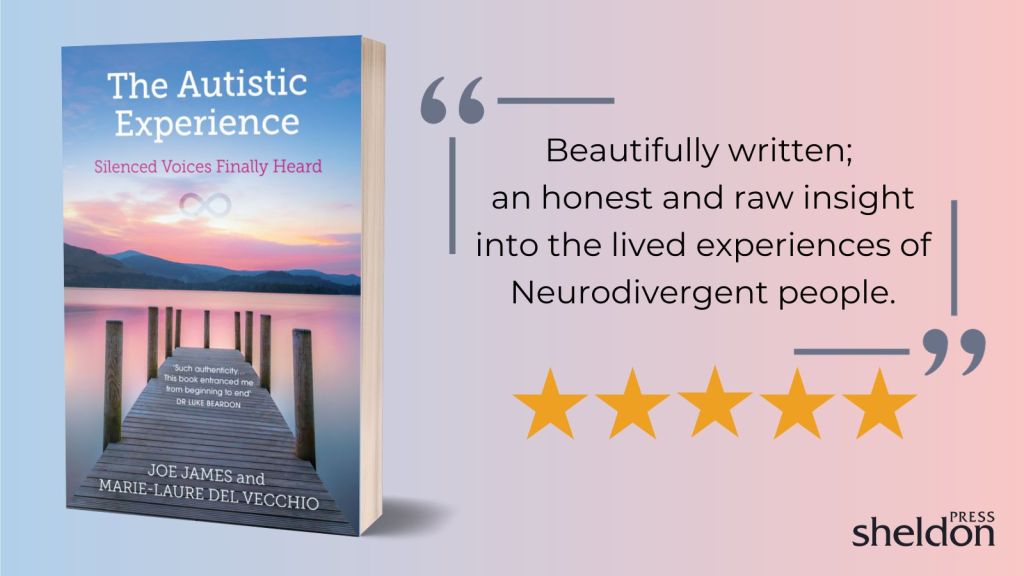

The Autistic Experience – book extract

The Autistic Experience skilfully collates an array of autistic voices on a range of topics, showcasing the breadth and variety of autistic experience. In this extract, taken from Chapter 3: Diagnosis, co-author Joe James describes the process he underwent to receive his diagnosis as an adult. From noticing shared traits with a child on TV, to informing his work of his official diagnosis, this is Joe’s story.

I was watching television with my wife, Sylvia. We were snuggled up on the sofa watching a programme about children who had ‘challenging behaviours’. Much of the time, it was the parents who I found to be challenging as they completely ignored their child’s obvious difficulties and chose to blame autism. It was called Born Naughty on Channel 4. The doctors on the programme visited the families to assess if the child was Autistic, had ADHD or whether they just had bad parents. I don’t know why it couldn’t be both, or neither, but that was the show.

I’ll admit I knew nothing about autism or Asperger’s and only a little about ADHD, even though I apparently had it. I had never been given help at school after my hyperactivity diagnosis and pondered whether it was even real, as no one in my family ever mentioned it to me. It was almost as though if I was hyper, it was my fault because I like chocolate, so it was my responsibility to control it.

So, there we were, three episodes into the series and a little boy called Thomas appeared. He was sweet, chatty at you not with you, liked Lego, had siblings but would only play with them if they joined in with his games, was constantly running around and seeking stimulation, and rarely listened to his parents. He tended to be quite violent and would have very destructive meltdowns. He was nine and had been so badly bullied he refused to go to school. My wife’s eyes darted towards my face, then back to the television, then back to my face.

‘What?’ I asked as she stared at me, aghast.

‘This boy is you!’ she said.

‘How?’ I always listened to her, even if I didn’t always agree with her.

‘Just watch it again, he’s just like you when you were a child.’ She would know as my family always spoke about how ‘difficult’ I was and how much of a ‘pain’ I was. Sylvia didn’t like hearing this stuff, but she put up with their bashing of her husband because she hates confrontation.

I obliged and pressed rewind on the remote. We watched again and this time I concentrated much more and intently analysed Thomas, not what they were saying about him. People had said stuff about me all my life, so I didn’t want to hear their thoughts. I watched him, watched his movements, his eyes, his passion when talking about Lego, his face drop as he spoke about friendship. My eyes began to water, my stomach turned, I had flashbacks to my childhood and there it was, Sylvia was right. I paused the show and looked at my best friend.

‘He’s just like me!’

‘Does this mean you have autism?’ That’s what the programme called it.

‘Let’s watch and find out if the doctors think Thomas does.’ We hadn’t actually got that far at that point.

Suddenly it was like I was being diagnosed myself. I heard words like ‘medical condition’, ‘behaviour problems’, ‘underlying problem’, and those words made me angry. I didn’t feel like I matched any of these phrases, and neither did Thomas. I wasn’t a problem, the way I was treated and the environments I was forced into were the problem.

We watched on tenterhooks as the parents sat at a table with the doctors and Thomas played with his Lego. The results were in and they were told Thomas was on the Autistic spectrum and was ‘high-functioning’. I remember thinking this was an odd way of describing it, as then they went on to tell the parents all the help he needed. If someone was high-functioning, surely that meant they were better than average-functioning, so who was average?

So, there it was, the answer to why all my life I had felt so different from everyone else. The reason I struggled to fit in, even as an adult. The reason I fell out with work colleagues, friends and family. The reason I struggled to socialize and lost my temper and hurt myself. The reason for all my problems became very clear. But I didn’t blame my autism for those problems, I blamed everyone else, for the way I was treated.

Even though I didn’t have a formal diagnosis I went into full-blown research mode and found out everything I could about autism. There was a lot of information out there and most of it contradicted itself. I found out that the type of autism I had was called Asperger’s, named after a doctor who called his patients ‘little professors’. I quite liked that as it fitted the way I felt about being an ‘Aspie’. I was highly intelligent, loved science, art, documentaries and research. It was all falling into place. I spoke to some of my siblings and even my parents. My dad said I was just Joe, my sister and younger brother said it made sense, my birth mother said she had suspected for some time. Wait, what? I asked why she hadn’t said anything and she told me she thought I was doing fine, so why upset things? I could have screamed. Years and years I’d felt out of place, Sylvia and my nephew Jake being the only ones who understood me and apparently the answer to my lifelong question ‘Why me?’ was on the lips of my so-called mum all along. I don’t know if she was trying to be smug, supportive or vindictive, I could never tell with her.

Sylvia thought it would be a good idea to get a formal diagnosis because I’d had some fallings out at work and she wanted to make sure I was legally protected by the disabilities act. I agreed, as I do most of the time, her feelings and worries trumping my opinions on the subject. I went to my GP (general practitioner) and chatted away, barely letting her get a word in edgeways, and she agreed very quickly with my well-put analysis of my life to this point. I was lucky to have a GP who understood autism and who didn’t think it was all about rocking in a corner and lacking empathy. With me, I had a small library of proof of my self-diagnosis printed out from the internet, but it turned out I never needed it.

A few months later, I was chatting with a lady from the local mental health clinic. I couldn’t understand what it had to do with mental health, but I just took it in my stride. She asked me about my childhood, she asked me about my friendships, I told her about my special subjects and saw her smile slightly as she clearly made up her mind that I was indeed an ‘Aspie’ (I now know better and despise the terminology). It took her just over an hour and she confirmed the diagnosis. She said, ‘Welcome to the club’, which I really liked, and made me feel like I wasn’t alone as I had once thought. She told me about services and a support group, I told her that none of that was necessary, but I was interested in some more information. We booked a follow-up appointment which I missed due to being easily distracted and she never replied to the voicemail of apology I left her. I decided that she was too busy for me and to just get on with it myself.

That was it then, I was officially Autistic (Asperger’s), my paperwork said. I messaged everyone I knew a photo of the signed paperwork, almost rubbing it in their faces how wrong they had been to judge me as they had. I felt vindicated, relieved and bitter at all those who had ignored me and made me feel bad about being different. I told everyone I knew, even my trainer at the gym. I was really proud and kept reminding them about Charles Darwin and Albert Einstein who were said to also be Autistic like me. I truly saw the positives, but not everyone I met had the same opinion.

When I informed my manager at work, he told me to keep it to myself. He told me it could negatively impact how people perceived me or stop me from getting promoted within the company. He said that people would see it as a weakness and not take me seriously as a supervisor any more. Luckily for me, I ignored him and at least for the next few years I remained positive about my new-found understanding of who I was.

My dream for the future is that being Neurodivergent will not be seen as a diagnosis but as a type of person who experiences the world differently and each individual will get support based on their specific needs and not as a blanket label. We should discover our neurotype and embrace who we are.

The Autistic Experience: Silenced Voices Finally Heard is available now.